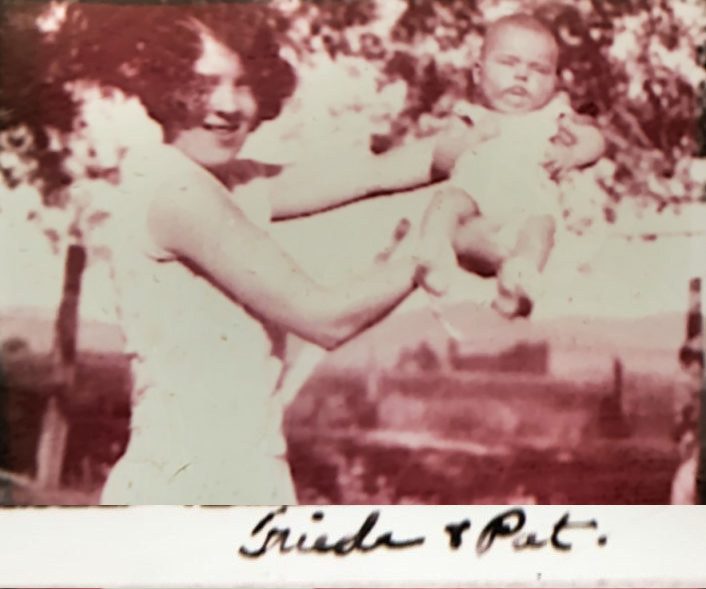

My maternal grandmother was named Frieda. I just found out from Wikipedia, that saucy mistress of procrastination, that the name means “peaceful ruler” and I have to say that is spot on. She was a wonderful mix of autocratic and kind and the reason I do what I do in the way that I do is all about her and the values she lived in — they are written into my very genome.

She taught me to drive in a 1972 Nova with no power steering or power brakes, swear and count to ten in German, make fudge, enjoy movies, and create a family table where everyone is welcome. Once when she was driving me somewhere and taking her time, a car shot past us yelling “go home old lady!” and without missing a beat she shouted back “go to hell young man!” She smoked exactly one cigarette a day up until she died at the age of 86 and god help you if you felt chatty during this sacred time. She refused to go to the senior center or assisted living home because “there were too many old people there.” She died in the bedroom of her small house, surrounded by family and a fence with posts in a less than a straight line because she kept bringing my uncles and cousins beers as they were building it. I still laugh to remember the squirrels falling off as they attempted to run across the top of the “drunken fence”, surprised by the deviations from the expected every time.

The Frieda story I keep returning to right now, in the middle of the uncertain road that is unfolding before us, is the story her children tell about growing up with Frieda in the little town of Baker, Oregon in the 1920s and 1930s. Baker was a train town, and the Moody’s were its cattle royalty until the stock market crashed and the great depression emptied their coffers and scattered those of working age to the winds. My grandmother had come to America when she was 12, and at 17 married into the Moody clan. When the great depression hit, her husband Kenneth went to work on the docks in another state. I’m being kind when I say that he drank a bit, and was absent-minded about sending money home to his wife and family. Frieda, in her early 20s with four children under the age of six and a mother-in-law who was by every account “difficult”, was left to fend for herself and those in her care. Frieda went to work in the local bakery, took in washing, and rented out rooms in their home.

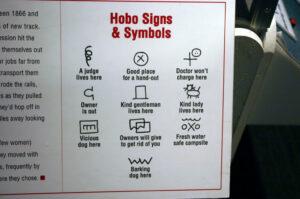

In those days, train towns hosted a lot of migrant laborers, colloquially known as hobos, traveling through and looking for work and living rough near the train yards. They would make a daily pilgrimage down the residential alleys to ask for work, food, help, a handout, and all the while trying their best to avoid trouble in an unfamiliar town. They would chalk the alley gates with symbols for those following them to read and take notes. Frieda, with all those kids, an absent husband, and a difficult mother-in-law, had a large piece of chalk she kept near the back door. After rain or bad weather, she would make her way to the alley gate to ensure that the chalk mark saying that this house had enough to share had not washed away in the storm. Frieda didn’t like to talk much about the past, she always had her eye on the now and the “what’s next?”, but she would say when asked about this ritual that she was dedicated to having a life so full, so abundant, that there was always a bit of extra. That potato, or a scrap of bacon, would travel in a stranger’s hands (as she had once been a stranger) to be added to a soup that would feed many down near the train yards. It was her church, her tithe of gratitude for always having just enough to share. It made her feel that her life had meaning and purpose that stretched beyond the boundaries of her day-to-day existence.

In those days, train towns hosted a lot of migrant laborers, colloquially known as hobos, traveling through and looking for work and living rough near the train yards. They would make a daily pilgrimage down the residential alleys to ask for work, food, help, a handout, and all the while trying their best to avoid trouble in an unfamiliar town. They would chalk the alley gates with symbols for those following them to read and take notes. Frieda, with all those kids, an absent husband, and a difficult mother-in-law, had a large piece of chalk she kept near the back door. After rain or bad weather, she would make her way to the alley gate to ensure that the chalk mark saying that this house had enough to share had not washed away in the storm. Frieda didn’t like to talk much about the past, she always had her eye on the now and the “what’s next?”, but she would say when asked about this ritual that she was dedicated to having a life so full, so abundant, that there was always a bit of extra. That potato, or a scrap of bacon, would travel in a stranger’s hands (as she had once been a stranger) to be added to a soup that would feed many down near the train yards. It was her church, her tithe of gratitude for always having just enough to share. It made her feel that her life had meaning and purpose that stretched beyond the boundaries of her day-to-day existence.

I’ve carried that story and the values of my tough-minded loving Oma Frieda into all aspects of my life. It sustains me when things get difficult, it puts me back on track when I get lost or distracted. She lives in my own logo. This half-circle unfolds so much meaning for me. Like the simple chalk symbols on Frieda’s back gate, this image symbolizes for me the optimism and generosity, and belief that is at the very heart of my work. We are here for each other, we are stronger together, abundance is within reach and sharing makes it all the more nourishing. Our work has meaning when it connects us to others. Recognizing the unique place that each of us holds in this ecosystem of generosity; asking, giving, receiving, gratitude, and then honoring each of those roles as holding equal value and grace because, without each aspect, the fabric of our community would be less than a whole.

I’ve carried that story and the values of my tough-minded loving Oma Frieda into all aspects of my life. It sustains me when things get difficult, it puts me back on track when I get lost or distracted. She lives in my own logo. This half-circle unfolds so much meaning for me. Like the simple chalk symbols on Frieda’s back gate, this image symbolizes for me the optimism and generosity, and belief that is at the very heart of my work. We are here for each other, we are stronger together, abundance is within reach and sharing makes it all the more nourishing. Our work has meaning when it connects us to others. Recognizing the unique place that each of us holds in this ecosystem of generosity; asking, giving, receiving, gratitude, and then honoring each of those roles as holding equal value and grace because, without each aspect, the fabric of our community would be less than a whole.

Frieda has been gone for many years, but I still hear her good advice and salty rejoiners regularly in my own work and relationships. I imagine pouring all of this out to her after a long day — the global pandemic, questions on how she lived through the unimaginable in her own time, my own search for how to serve in the best possible way, my questions on the road ahead, how to make sure the mark of generosity she so indelibly chalked in my heart will not be washed away — and her thoughtfully lighting her evening cigarette, then telling me to be quiet while she enjoys it and considers. . .

Joyfully,

Patricia